Pointing Immigration in the Right Direction

My service as a U.S. consular officer in the late 1980s and early1990s quickly debased me of any previous open-borders ideas I might have had prior to that time. While serving as vice consul for the geographically largest consular district in the world, covering most of the South Pacific and part of the North Pacific, I came to realize how poorly our immigration system served the country. Our two-officer office – me and the consul, my immediate boss – processed some 21,000 non-immigrant visas (NIVs) and about 6,000 immigrant visas (IVs) annually. I personally handled about two-thirds of the NIV applications and about a third of the IV applications. To say that some of those IV interviews verged on the scary would be an understatement, and made me wonder about the quality of people we were admitting for permanent residence in the U.S.

What occurred to me then was that the U.S. badly needed to implement a points-based immigration system similar to what already was long in place in Canada as well as in Australia and New Zealand, and has since even been adapted by the UK. Not that it would supplant this country’s family-based immigration system, but rather would supplement it, while revising the family-based system of preferences. While other countries were getting the cream of the crop of immigrants, we were limited basically to what came over the transom with our chain-migration policies, and that was not always beneficial to the U.S.

During my tenure as vice-consul in Fiji, yet another seemingly hair-brained idea was introduced, the so-called Diversity Visa Program (DVP), better known as the visa lottery program. A brain child of Congress, it allowed people from many countries deemed to be “under-represented” among U.S. immigrants to compete in a lottery to obtain the right to apply for permanent residence status. Besides debasing the whole concept of U.S. residency, this scheme essentially opened up a new category of immigrant visas to anyone who could fill out a postcard or pay someone to do it for them, as if we didn’t already have enough immigrants coming to the U.S., many with no discernible skills.

Over the intervening quarter century I have seen limited progress in immigration reform, combined with some steps in the wrong direction, acerbated by an ill-informed and prejudiced public and media debate over immigration. With this past week’s introduction of the so-called RAISE Act (RAISE – not Reyes – standing for Reforming American Immigration for Strong Employment), I am for the first time in more than 25 years seeing reforms introduced that actually seem to make some sense. And of course the naysayers immediately came out in force, spouting the same sorts of nonsense that have kept our immigration system stuck under a law that dates back some 65 years, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, as amended and modified by some less overriding intervening laws.

To begin to understand the forces arrayed against any real reform of our outmoded and ineffectual immigration policy, one needs to understand two truisms about what the major political parties hope to gain from immigration: The Democrats want cheap votes, and the Republicans want cheap labor. These two impulses are the biggest factors keeping things pretty much where they are, if not pushing them further in the wrong direction. And it is these same factors that are the biggest enemies of the American people at large and which help keep our economy in a low-growth mode in which real wages remain stagnant while the costs of the welfare state continue to grow.

It’s also important to understand that the U.S. is not a laggard when it comes to immigration. While it may no longer be strictly true that we admit more legal immigrants than all other countries in the world combined, it is true that we admit, by far, the largest number of legal immigrants each year – more than a million people – and that number does exceed the total number of immigrants admitted by all the other largest immigrant-welcoming countries of the world combined. At present, close to 45 million immigrants (both legal and illegal) live in the U.S. There are some 85 million people, or about 27 percent of the total population, who are immigrants or the U.S.-born children of immigrants.

There are a lot of myths and stereotypes about immigration and these help perpetuate our current system. One of those myths is that immigrants strengthen the economy and do better than native-born Americans. While this was once true, it has not been true in more than a quarter century, and since then, in general terms, immigrants tend to fare worse than the overall population. This fact is buttressed by the numbers that show that immigrants to the U.S. are far more likely to wind up in poverty than the native-born population. Here are some disturbing figures from the Center for Immigration Studies:

“Despite similar rates of work, because a larger share of adult immigrants arrive with little education, immigrants are significantly more likely to work low-wage jobs, live in poverty, lack health insurance, use welfare, and have lower rates of home ownership.

- In 2014, 21 percent of immigrants and their U.S.-born children (under 18) lived in poverty, compared to 13 percent of natives and their children. Immigrants and their children account for about one-fourth of all persons in poverty.

- Almost one in three children (under age 18) in poverty have immigrant fathers.

- In 2014, 18 percent of immigrants and their U.S.-born children (under 18) lacked health insurance, compared to 9 percent of natives and their children.

- In 2014, 42 percent of immigrant-headed households used at least one welfare program (primarily food assistance and Medicaid), compared to 27 percent for natives. Both figures represent an undercount. If adjusted for undercount based on other Census Bureau data, the rate would be 57 percent for immigrants and 34 percent for natives.

- In 2014, 12 percent of immigrant households were overcrowded, using a common definition of such households. This compares to 2 percent of native households.

- Of immigrant households, 51 percent are owner-occupied, compared to 65 percent of native households.

- The lower socio-economic status of immigrants is not due to their being mostly recent arrivals. The average immigrant in 2014 had lived in the United States for almost 21 years.”

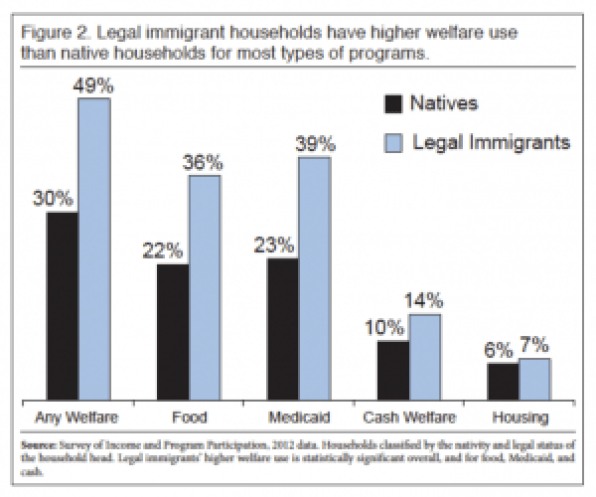

While laws are in place that are supposed to limit immigrants’ access to welfare and other public assistance programs – the idea being that newcomers to the country are supposed to be able to support themselves, or have sponsors that will support them until they can support themselves – so many exceptions are made, so many jurisdictions overlook the rules, and so many benefits are obtained through the U.S.-citizen children of immigrants, that immigrants tend to use social welfare programs at rates in excess of the native population. The two charts that follow (also from the Center for Immigration Studies) clearly demonstrate the numbers. The first one compares legal immigrants with the native population while the second one compares illegal immigrants, who do even worse and aren’t even supposed to be here, with the native population.

Another key element that is widely misunderstood, further evidenced by some of the silly things said in the days since the RAISE Act was unveiled, is the system of preferences under which our current immigration system operates. This system imposes strict numerical caps on different categories of immigrants from various countries, and creates serious distortions that those only peripherally familiar with the rules don’t understand. For instance, while there is no cap for the spouses or unmarried minor children or the parents of U.S. citizens, 21 years old and older, there are limits for just about every other category of immigrant.

The chart below shows the current (August 2017) preference limits for the various preference categories. It shows the dates when petitions would have had to be filed for intending immigrants in those categories, or preferences, to file their applications this month to be approved for immigrant visas. Depending on the country, these dates can vary significantly.

For instance, for the first preference, the unmarried son or daughter, 21 years or older, of a U.S. citizen (native-born or, more commonly, naturalized), their petition would have had to be filed prior to 2011 in most countries of the world to file their applications for visas beginning this month. But if they are a citizen of the Philippines, the petition would have had to have been filed in 2007, or in 1996 if they are a citizen of Mexico. In other words, perhaps the beneficiaries were 22 or 25 or 27 when the petition was initially filed, but now they are anywhere from 10 to 21 years older. And these time periods don’t include processing times, which can be a year or more, once the application is filed.

If the applicant subsequently marries after the petition is filed, they drop to the F3 category and the preference dates of it.

For a second preference applicant in the F2A category – the spouse or unmarried minor child of lawful permanent residents (LPRs) – the wait has been a little more than a year worldwide. Not too bad. But for the unmarried son or daughter of an LPR who was over 21 when the petition was filed, the wait jumps to six years for most countries, 10 years for citizens of the Philippines, and 21 years for citizens of Mexico. If that unmarried minor child subsequently marries, they’re completely out of luck since there is no category for married children of LPRs.

As the chart shows, things get worse as one goes down the preference categories, until reaching F4, the preference category for brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens, when the wait can be as long as 22 years. Now that is a lot better than when I was a consular officer, when the wait for some countries was as long as 120 and 150 years, but it’s still a very long time. In practical terms, what these very long wait times do is encourage people in those categories to come on visitor visas to the U.S. and then overstay their visas, hoping to find some other mode to become legal.

In fact, more than half of those qualifying for immigrant status are already in the U.S. in some sort of temporary or illegal status, changing status when their preference comes up or simply remaining illegally if their preference never comes up, which distorts the entire system and enables those who are willing to jump the queue and break our laws to gain an advantage.

Seeing the effect these very long wait times have on people, it has been my contention since my consular days that the brother/sister category should be eliminated altogether. And that is one of the things the RAISE Act sensibly does, along with dispensing with the DVP, which never should have been introduced in the first place. I’d further argue, to cut out much of the incentive for overstaying, that changing status in the U.S. also should be strictly limited to those categories of immigrants for which no preference limits exist.

What is very difficult, if not impossible, under our current system of chain migration is to migrate independently to the U.S. – something that once was allowed and frequently done. There are many highly qualified potential migrants who would love to immigrate here, but who are blocked by our system of family preferences. So what happens with many of these people? They wind up migrating to another country, and our loss is Canada’s or Australia’s or New Zealand’s gain. The same applies to graduates of U.S. colleges and universities who study under student visas and then are forced to go back home after graduation. We’ve educated these people, and then don’t reap the benefit of that education, passing it on somewhere else. Again, these are exactly the kinds of people we should be seeking through our immigration system, and who will gain points under the RAISE Act.

One of the dumbest arguments I heard this week came from U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina. He said that the RAISE Act would destroy his state’s economy by blocking lower-level employees who work in hotel and agricultural jobs. First of all, if those are the only kinds of jobs available in the Palmetto State, South Carolina has more serious problems than the RAISE Act would cause. Of course, that’s not true, and there are more jobs in South Carolina and across the land that can use more highly skilled people to fill them. Additionally, there already are programs, such as the H-2A temporary agricultural worker visa, to address the demand for agricultural workers, not to mention a ready supply of illegal workers that Republicans like Sen. Graham seem all-to-eager to tolerate. Sen. Graham’s assertion actually reinforces the argument that our current immigration system funnels people into lower-level positions and helps depress wages across the board while forcing lower-skilled U.S. workers to compete with immigrants, legal and otherwise, for scarce jobs. It also fits neatly into the theory that Republicans support cheap labor.

Meanwhile, we’ve heard a chorus of objections from the Democrats, reinforcing the theory that nothing suits them better than easy, low-level immigration from which they hope to harvest cheap votes. Perhaps encapsulating some of the lame arguments on the left side of the house are that the RAISE Act invalidates the poem on the Statue of Liberty welcoming the world’s huddled masses – never a tenet of U.S. immigration policy or law – or that immigration would be limited to Anglophone countries, such as the UK or Australia, since knowledge of English would be one of the requirements for independent migration. As White House Senior Policy Adviser Stephen Miller ably pointed out, there are many English-speaking people around the world in just about every country, and all would be able to meet the language preference. Additionally, knowledge of English has long been a requisite for naturalization, and at one time in our more distant history was even a requirement to immigrate here.

In the past few days I’ve also heard some media people saying, well, they wouldn’t be here if the changes proposed in the RAISE Act were in place when their grandparents migrated here, and I fail to see the logic of this. First, they are here. Second, while they might be here, someone else, perhaps equally worthy, was excluded. And third, what might have been good for the country 100-some years ago isn’t necessarily good for the country today. Ironically, some of the people making the argument that we should keep our current system are the first ones to argue that the country is a different country today than it was in the past and it needs to change to keep up with the times.

The other argument that is raised is that the actual numbers of immigrants admitted would be cut from the current million-plus to about two-thirds that number, or roughly back to mid-1980s levels. This might be more in keeping with the ability of the country to absorb new immigrants, but in any case this number seems reasonable and can be adjusted over time. It is argued that the high level of immigration has kept the U.S. relatively competitive with European countries and other nations, but what is missing from that argument are the details that it is both younger immigrants and more highly skilled immigrants who can contribute to economic growth, rather than draw down on it. We need to regenerate a period when immigrants do better than the general population, as in the past, than worse than the general population, and the RAISE Act is a step in that direction.

Like any piece of proposed legislation, there should be debate and discussion, and probably some tweaks made, to the RAISE Act, which is sponsored by Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas and Sen. David Perdue of Georgia. But what I fear will happen will be bipartisan support to kill the proposed reforms, never letting the bill out of committee, in keeping with the divergent desires of the two parties that I stated above: The Dems will want to keep their cheap votes and the Republicans will want to keep their cheap labor, and the rest of us, and the country, will continue to suffer as a result.

This piece also appears on Medium. Follow me there, and here, and if you like the post please comment and share it.